Many features differentiate comics, cartoons, and graphic novels from other literary and visual media (not to mention from each other). I encountered the term Sprechblasenliteratur—“speech-bubble-literature”—in Andreas C. Knigge’s Fortsetzung folgt (287), and as a blanket term for comics, comix, comic strips/cartoons, graphic novels, etc., I think it’s just delightful. However, the term is not without shortcomings. For instance: what do we call works that are clearly comics but that do not contain Sprechblasen (speech bubbles)?

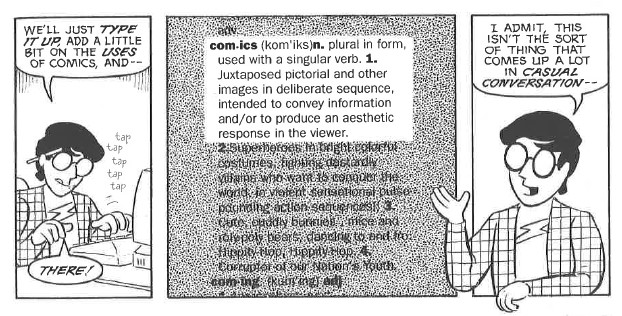

McCloud presents the following definition of comics in Understanding Comics:

The essentialness of the image is key, not necessarily that of the speech bubble—in fact, McCloud’s definition does not state that sequential art must include words, in speech bubbles or otherwise. This is quite in contrast to David Carrier’s conception of comics, in which the speech bubble (he calls them “speech balloons”) is what makes comics comics: “The speech balloon is a defining element of the comic because it establishes a word/image unity that distinguishes comics from pictures illustrating a text, like Tenniel’s drawings for Alice in Wonderland.” In his view, then, comics “are essentially a composite art: when they are successful, they have verbal and visual elements seamlessly combined” (4). Under this definition, however, would a wordless creation such as Shaun Tan’s graphic novel Arrival be considered a “comic?”

For Theirry Groensteen, the defining characteristic of comics is “iconic solidarity” (emphasis in the original). This he defines as “interdependent images that, participating in a series, present the double characteristic of being separated … and which are plastically and semantically over-determined by the fact of their coexistence in praesentia” (18). As near as I can tell, Groensteen’s definition is a fancified version of McCloud’s, though Groensteen goes into far more detail concerning this definition in the ensuing 150+ pages of The System of Comics.

It seems, then, that no one completely agrees on how to define comics—and perhaps this is how it should be! Comics are a genre-bending artistic medium, and the mere fact that not all comics combine sequential images with words is enough to stymie definition. I agree with Eckart Sackmann when he writes: “Die Frage der Definition ist noch längst nicht geklärt, und es scheint wahrscheinlich, dass sie nicht abschließend geklärt werden wird” (“Comics sind nicht nur komisch” 16). For my part, I enjoy the term Sprechblasenliteratur, but I will be using “comics” as a blanket term for cartoons, comics, comic strips, and graphic novels throughout the course of this blog. I will do this largely for the sake of consistency with the other fine thinkers and theoreticians who study these artistic forms, but also in part because “comics” takes much less time to write and read than “Sprechblasenliteratur.”

We might not be able to define “comics,” but we generally know them when we see them. And one of their most distinctive features is the visual representation of sound. In fact, Joseph Witek goes so far as to say that “the conspicuous verbal/visual role of … sound effects epitomizes that blending of word and image which distinguishes sequential art as a literary medium” (44). The representations of sound in comics are so commonplace today that we don’t even think about them anymore—the sound effects of the old Batman comics come to mind. These were such an integral part of the comics that they were even imported into the TV adaptation! But the representation of sound in comics has a storied history, and the amount of innovation in the visualization of sound by present-day comics artists is incredible and, frankly, tremendously exciting. In short, it’s a great time to get into “Comics Studies.”